By Bill and Melinda Gates

Stunting is one of the most powerful, but most complex, measures in global health.

Stunted children are defined as children who are short for their age by a specified amount. But it’s not actually a child’s height we’re concerned about. Rather, stunting is a proxy for something much more important: how children are developing cognitively, emotionally, and physically. Stunting is the opposite of well-being, which is why we say it’s such a powerful measure.

But it's complex because it’s caused by multiple factors that accumulate over a period of time—everything from a mother’s health to a child’s diet, disease history, and environment. We don’t yet have a complete picture of the root causes—and there is no single intervention to prevent it. We have to mix and match a variety of interventions. We have spent a lot of our time recently speaking to global experts to learn more about stunting and its solutions. As development experts and practitioners continue to build the evidence base, however, countries need to scale up the set of health and nutrition interventions already proven to reduce stunting significantly.

Peru’s story is impressive because they cut through a lot of that complexity and focused on what we know works. Peru proved that stunting is a solvable problem when leaders are committed to following the evidence.

We asked Milo Stanojevich, the national director for CARE Peru, and Ariela Luna, former deputy minister of development and social assessment, to write short essays explaining how the country made so much progress in such a short time.

Milo Stanojevich

National Director, CARE Peru and Chair, SUN Civil Society Network

I grew up in Peru, left for a while, and came back home after 13 years, in 2005, to find it was a different country, a middle-income country.

But we still had the malnutrition rates of a low-income country. The government had been trying to address the problem with traditional feeding programs, but interventions that didn’t address health and nutrition more broadly were never going to work.

CARE Peru had just ended a large program, funded by USAID, that took a different approach. We’d combined a range of nutrition, food security, water and sanitation, and health investments in 1,200 communities, and the results were just amazing. We reduced chronic malnutrition in those communities by 10 percentage points. We wanted the government to take up the lessons we’d learned, so, working with other NGOs and UN agencies, we formed the Child Malnutrition Initiative just in time for the 2006 presidential election.

We explained to the candidates that stunting was the core of poverty in Peru—that having 30 percent of children chronically malnourished put a huge dent in the whole country. We also showed them our evidence about a package of interventions that worked. Clear problem, clear solution. We got all the major candidates to sign what we called the 5x5x5 commitment: a pledge to reduce stunting among children under 5, by 5 percentage points, in 5 years.

When Alan Garcia was elected president, the prime minister ratified his commitment in a speech to Congress. We were euphoric. The government was promising to fight chronic malnutrition in front of the entire Peruvian public on TV. In fact, President Garcia eventually pledged to do even more—to reduce stunting by 9 percentage points, a goal he achieved. Nutrition was indeed a national priority.

In 2011, the government changed, and we did the whole thing all over again. And again last year. We wanted to get a question on nutrition into the presidential debates, so we tapped our networks and got 2,000 people to send in the same question to the election board. The moderator asked it: “What will you do to continue reducing chronic malnutrition in the country?”

We are proud of our advocacy, but advocacy alone does not take programs to scale. You have to design programs that fit in with the way government works. We didn’t have all the answers about how to do that. But we knew that it was essential to have the highest-level political commitment, more investment for nutrition, and a strategy that coordinated interventions across ministries and different levels of government. We just kept the pressure on and kept the support through three different administrations, and the government made it happen.

Corn, seen drying on lines outside homes, is an important local source of nutrition. (Sogobamba, Peru)

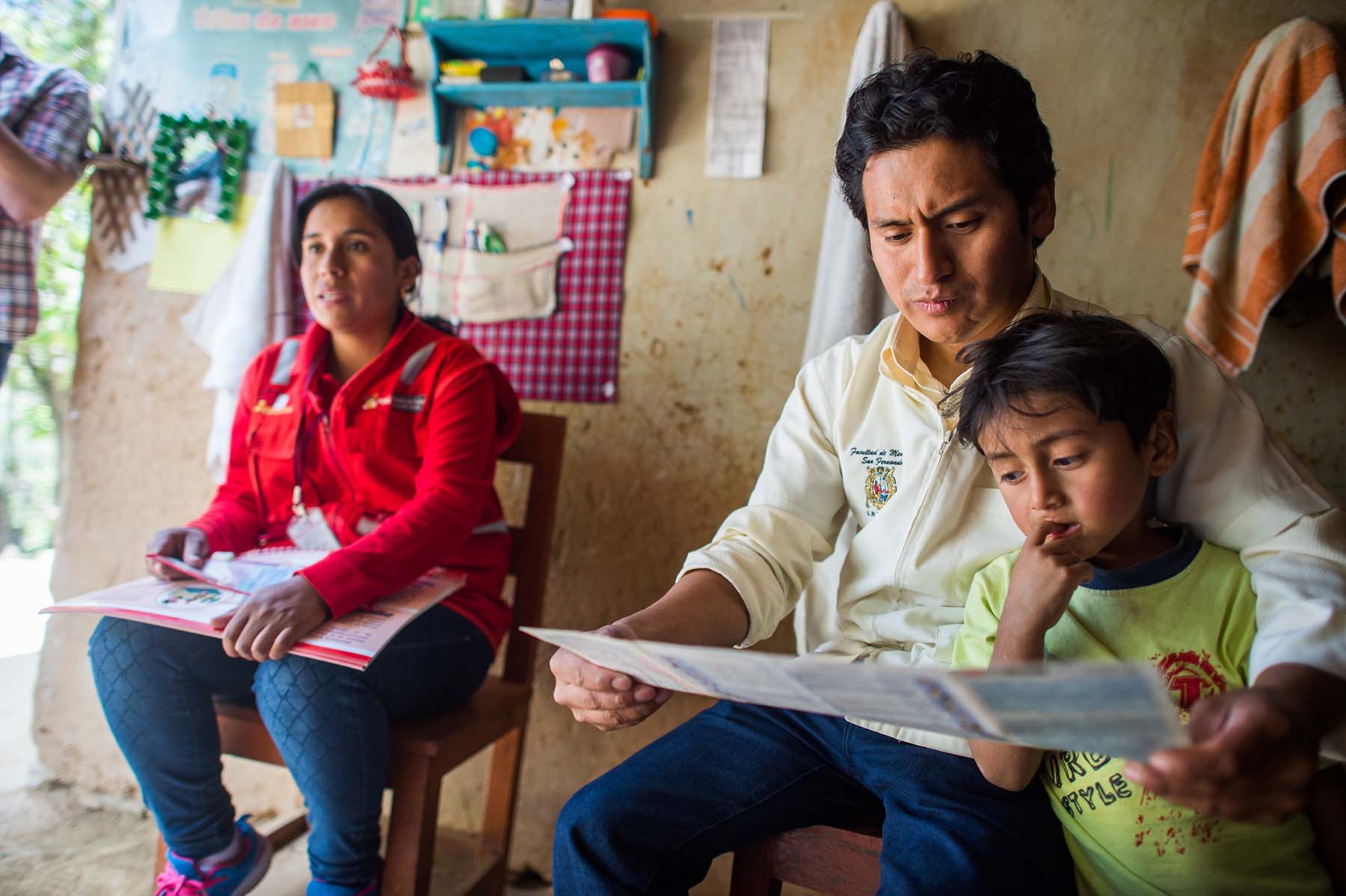

Health care workers review the growth chart of a child while speaking to a mother during a home visit. (Sogobamba, Peru)

Health care workers use a tablet to collect health and development data while speaking to a mother about her son during a check-in visit. (Sogobamba, Peru)

A health care worker explains a children's growth chart at a local maternal and child community center where health workers track interventions and weight of each child under 3. (Sogobamba, Peru)

A mother holds her infant son's head during a height measurement at a local health clinic. (Potracancha, Peru)

A nurse measures the head circumference of a girl at a health clinic to compare her development with international averages for children her age. (Acomayo, Peru)

A nurse measures the height of a boy at a health clinic during a regular checkup. (Acomayo, Peru)

Nurses from a local health program counsel a mother on how best to care for her young children. (Acomayo, Peru)

Parents learn good feeding practices such as exclusive breastfeeding during the first months and supplementary feeding with locally available food in the months that follow (Lima, Peru). (Photo courtesy of CARE)

Ariela Luna

Former Deputy Minister of Development and Social Assessment, Peru

We started by designing a causal model for reducing chronic child malnutrition based on the available scientific evidence, and we got all the stakeholders to agree to it.

Next, we prioritized two cost-effective, high-impact interventions: child vaccination and counseling for mothers, to help them understand how to keep themselves and their babies healthy and well nourished during the 1,000 days from conception to the child’s second birthday. You can design a wonderful program with two dozen interventions, but you’ll never get it off the ground. It was important to prioritize and reprioritize.

The health sector worked very effectively with the Ministry of Economics and Finance. We implemented a results-based budget strategy and created the Articulated Nutritional Program, which allowed us to rearrange the existing budget and refocus it toward chronic malnutrition. That was what convinced the Ministry of Economics and Finance. They tend to say, “If this is going to cost a lot, we’ll stay out of it,” but nobody will stand against initiatives for children when the solutions are proven and affordable.

When we started to implement the program, we targeted the areas in the country where stunting rates were the highest. In those regions, we started budgeting based on the needs of each health care center and tracking the results. When I traveled to any region to supervise the coverage, they couldn’t lie to me, because we kept evaluating them, not just once every year, but every day if possible.

Nobody will stand against initiatives for children when the solutions are proven and affordable.

Our ability to measure results also helped us to provide incentives to regional governments that performed well, which accelerated progress. First, we withheld a small part of the Ministry of Health’s budget until the regions met key targets. In six months, almost 100 percent of the country’s regions were carrying out best practices that had been neglected before.

We also gave extra money to regions that invested in the infrastructure they needed to meet the goals we’d agreed upon. In order to make a shoe, you need leather, scissors, and workers. And to implement a vaccination program, you need nurses and supplies. Regions got more budget when they put those pieces in place.

With these two incentives, we could be certain that health care centers were fit for the day-to-day work. And the day-to-day work changed life for Peru’s children.

We are now a country that managed to redirect its resources to help millions of children break free from chronic child malnutrition. And the best of all, chronic malnutrition in Peru keeps going down.

The stories behind the data

© 2017 Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. All Rights Reserved.